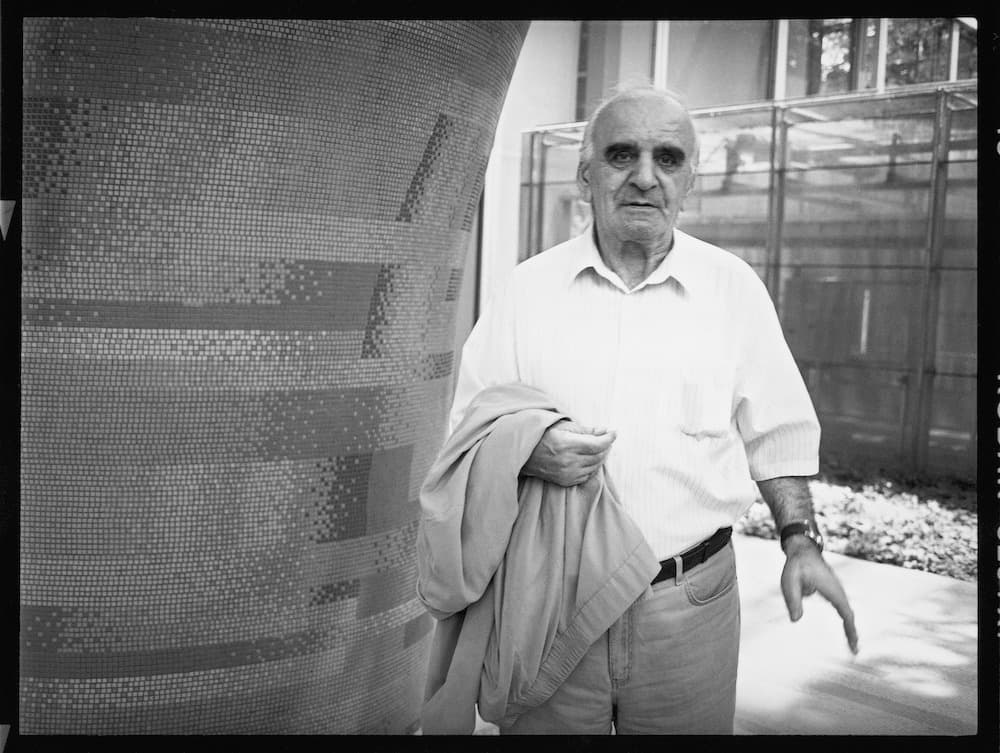

The afterimages of Artavazd Pelechian

This year, IDFA presents a special program around the Armenian filmmaker Artavazd Pelechian. After seeing Artavazd Pelechian’s films it seems as if everything in his films is interlinked. As if everything you see and hear is in conversation with everything else. Without a single word being spoken, and without us entirely understanding why, Menno Otten argues.

In the opening sequence of Seasons of the Year (1975) by Armenian filmmaker Artavazd Pelechian (1938), we watch a shepherd being spun around his own axis as he struggles to keep his sheep above the churning water of a raging river. Accompanied by the music of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, the shepherd fights for all he’s worth to save the sheep – and himself – from drowning. As unfathomable as this following scene is in itself, the way Pelechian edits it is equally so.

This series of images is one of the most intrusive I have ever experienced in the cinema. By which I mean: over the years, these images have taken root in my memory and now behave like an – almost – real memory.

The most remarkable thing, however, is that I have no memory of my first experience of watching these images. I probably saw one of Pelechian’s films as a student at the Film Academy: but I have no recollection at all of what the film was about, or its chronology. Perhaps even stranger, in retrospect I am unable to talk about the story of any of Pelechian’s films – even after having seen them for a second or even a third time. While this is a filmmaker who forever changed the way I see filmmaking! It’s as if I have never been able to find the words for the way his films move me. Perhaps this is related to the wordless nature of his films; it’s not often we come across an entire film oeuvre in which the number of sentences spoken can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

I once read, in one of the rare interviews Pelechian gave, that he is convinced that cinema is able to put across certain emotions that cannot be expressed in any language anywhere in the world. According to Pelechian, the existence of the word comes from human interaction, while our existence as humans comes from nature. And what Pelechian is all about is dealing with our natural essence. Which is why, almost without exception, his films deal with the relationship between man and nature.

This relationship between man and nature is something that, after seeing Pelechian’s work, it is easy to talk about. In Seasons of the Year, this means the struggle, and the harmony, of shepherds in a village in Armenia amidst the four seasons of the year. In We (1969), it is the relationship between the Armenian people and the land, from which the marvellous Armenian in the film seems to be born. In Inhabitants (1970), it is the rhythmic relationship between wild animals and humans. And for his most recent work, the completely archival film Nature (2019) – Pelechian spent more than 25 years working on a new film – it is the devastating force of nature, putting humans in their place.

When I close my eyes after seeing Pelechian’s films, what remains – alongside a powerful stream of emotions – is above all a stream of images in my mind’s eye. Afterimages in which man and nature become one; but I am unable to re-tell any single, unified narrative. The fact that I do nevertheless experience his films as a single entity, as a single narrative or one single emotion, is I believe above all related to the way Pelechian edits his films.

In a sense, Pelechian responds in his editing method to predecessors such as Lev Kuleshov and Sergei Eisenstein, both of whom taught and studied at VGIK, the same film school in Moscow where Pelechian studied. Kuleshov and Eisenstein played with the power of editing to give signification and meaning to what we see in film. A shot of the face of a man looking at a (next shot) bowl of soup, suggests to us viewers that the man we just saw – you get it I’m sure – is hungry. The one shot relates to the next. The editing connects the two and so gives meaning to what we have seen. And it is this way of editing that has strengthened the incredible grip cinema has on the viewer’s consciousness. Editing is what makes it possible to allow images to lie, and in so doing tell the truth.

But whereas Eisenstein and Kuleshov, and many others following in their footsteps, give meaning to their images by placing shots close together, Pelechian does this with shots that are far away from one another. And whereas for Pelechian’s predecessors every shot in the film should mean something, for Pelechian the individual shots mean nothing: it is only as part of the film as a whole that the shots take on meaning. In his book My Cinema (1988), Pelechian describes this editing technique as distance editing.

Which means that a perhaps indefinable shot at the beginning of one of Pelechian’s films might take on another meaning much later in the film. Because we see the shot again, or a little differently, that shot is now fed by what we have seen in between the two series of images: the shepherd struggling to keep his sheep above water in a churning river at the beginning of the film, much later in the film may slide down a snowy mountain with his sheep. Perhaps it is because, as a viewer, I edit the two scenes together in my head and so link them together, that these series of images become so deeply rooted in my subconscious, where they make an overwhelming impression.

However incomprehensible the above might seem: after seeing Artavazd Pelechian’s films it seems as if everything in his films is interlinked. As if everything you see and hear is in conversation with everything else. Without a single word being spoken, and without us entirely understanding why.

But, ultimately, how important is it really that we understand a film; that we are able to re-tell its story? Ultimately, what we long for most is images. The powerful memory of the images that remains once you have seen one of his films, means that from that moment on all you will yearn for is images as stunningly beautiful and unfathomable as those of Artavazd Pelechian.