A Personal Pathway: The Rise and Fall of Yugoslavia

This year at IDFA, there is an unprecedented number of films that deal with the history and breakdown of Yugoslavia, the country where I was born 44 years ago. These six new titles form a Pathway, called "Imagining Yugoslavia", along with Heddy Honigmann's 1999 film Crazy.

How is it that in 2022 we suddenly have, at the world's biggest documentary film festival, such a selection of films that deal with the trajectory of a relatively small country that fell apart 30 years ago? Moreover, five of them come from Serbian filmmakers, an industry that is tiny in the global context.

For one, it is a generational issue: all these filmmakers were born in Yugoslavia and grew up as it was falling apart. Now, they are reaching creative maturity, which is coinciding with the consolidation of Serbia's documentary scene and its increased co-production capacity. This is also the moment when, on a global level, many of the issues that these films deal with, including colonialism, imperialism, shifting ideologies, and the meaning of democracy, are being intensely discussed and questioned in the documentary field and the society as a whole.

At the beginning of Biserka Šuran's Envision Competition film Scenes with My Father, in which she talks to her father about why and how they left Croatia to move to the Netherlands, he asks her, "Why did you decide to make a documentary about such a marginal topic? It’s something that interests you, but why would an international audience care?" Placing this film in the Envision Competition and presenting the Imagining Yugoslavia Pathway hints at an answer: it is part of a much bigger, global narrative—one that IDFA wants to explore from all possible angles.

Yugoslavia at its peak

Five years after winning the top prize at IDFA with The Other Side of Everything, Mila Turajlić returns with an epic diptych that shows Yugoslavia at the peak of its global reputation: Non-Aligned: Scenes from the Labudović Files (International Competition) and Ciné-guerrillas: Scenes from the Labudović Files (Best of Fests), in addition to the IDFA on Stage event Non-Aligned Newsreels: Fragments #2 – New Voices from the Summit. Stevan Labudović was President Tito's favorite cameraman from the Yugoslav Newsreels who accompanied him on his travels, capturing key historical moments. Turajlić's interest in the history of her country, and particularly the cinematic aspect of it, is what drives her filmmaking: her first feature-length film, Cinema Komunisto, dealt with the film industry under Tito. With such experience and expertise, she went deep into the Yugoslav Newsreels' archive to dig out, scan, and digitize the footage shot by Labudović. Some of it hadn't been screened since Labudović first shot it, and some had never been seen at all.

Ciné-guerrillas: Scenes from the Labudović Files

Accompanied by the director's voice-over—which fluctuates between the factual, personal, and dialectical—Non-Aligned shows us the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement. It came into existence in 1961 at the summit in Belgrade, and back then, it was somewhat clumsily called "Non-committed", which gave it a negative connotation readily exploited by the media of countries belonging to both sides of the ideological divide. Initiated by Tito, the movement proposed a third way in the midst of the Cold War. It gathered 25 countries and 17 liberation movements from the Global South, with the most significant figures involved including Egypt's Nasser, India's Nehru, Indonesia's Sukharno, and Ghana's Nkrumah. It would eventually comprise 120 countries and has never been officially disbanded.

Through Labudović's footage, Turajlić tells the story of liberation and resistance against the great powers, but also of solidarity between oppressed nations. Besides the inspiring images of these great statesmen coming together to create an alternative to a fixed, rigged system, what stands out today is the reaction from the Western media, also incorporated in the film. These excerpts show that in the last 60 years, and by extension, throughout history, the entitlement and arrogance of "big nations" have not changed. A French news report from the time dismisses the initiative as insignificant, implying that the leaders themselves are not that invested, while an NBC correspondent compares them to animals in the Belgrade Zoo. In addition to being a prime example of the oppressors telling the stories of the oppressed, this immediately made me think of Trump's statement about "shithole countries," which provoked widespread outrage, when this is in truth how the privileged really see developing countries.

The other part of the diptych, the breath-taking Ciné-guerrillas, deals with one of the very substantial ways the non-aligned countries collaborated. During the Algerian War of Independence, Labudović was sent by Tito to help the Algerians—who had no film industry and no real technical capabilities to produce films—to counter French propaganda. The footage he shot over three years in the war became newsreels that helped shape the global opinion, turning it against France. Turajlić’s film emphasizes the power of the image and reminds us of the importance of who controls the narrative.

Nostalgia, myth, and ownership of the narrative

There are several angles from which authors from the former Yugoslavia decide to tell the story of it, and a typical one is nostalgia. In Turajlić's films, this aspect is certainly present, even though, in her voice-over, she keeps questioning the viability of the whole project, if not its sincerity. Interestingly, it is more typical of films coming from Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina to have this nostalgic slant: the former led the wars of the nineties without any blood being spilled on its own territory, and the latter suffered the most in them. Maybe this is because Tito is still the most beloved historic personality in Bosnia, where a typical, certainly simplified notion, is that under the former president, we all lived as one nation and everything was okay. Tito's larger-than-life figure still permeates the cultures of the new countries, and three films in the pathway include the same iconic scene in which a news anchor in 1980 tells the audience: "President Tito is dead." Many consider this moment the beginning of the breakdown of Yugoslavia.

Scenes with My Father

One film that uses this clip while reminiscing in a nostalgic key is Šuran's Scenes with My Father. In it, she speaks with her father who, just before the war in Croatia, moved to the Netherlands from Istria with his three daughters and his Dutch wife. They discuss why and how he decided to leave, and how she, who was two years old at the time, in fact feels more nostalgic towards the old country than him. For me, a person from a country with a large diaspora, this is easy to explain: the less you know about a myth, the more likely you are to embrace it.

Šuran uses a performative element in her film, placing her conversation with her father on a theater stage, where they are dressed the same—presumably, in the kind of clothes that he used to wear when they left Yugoslavia. The theatrical approach seems to add a layer of distance between their memories and the audience, one that is perhaps analogous to the 30-year gap they themselves are experiencing.

Turajlić, on the other hand, addresses this gap in a different way. She re-purposes the old archive footage without physically reframing it and keeps the white, perforated part of the track in her film, on screen left, constantly reminding us of its authenticity but also of its temporal distance.

In many ways, Turajlić’s approach is about who is telling the story: in the 1960s, cameras typically didn’t have microphones and the sound was recorded separately. As a Yugoslav Newsreels archivist says in the film, it was more important what the official narrator had to say in voice-over than what the people in the footage really said. The effects of this method are particularly jarring in old French newsreels from Algeria, where the oppressors painted themselves as saviors who enabled progress in a so-called backwards country.

Eventually, Turajlić went to Radio Belgrade and dusted off the sound recordings from the Non-Aligned Movement summit, producing unique material that includes the movement's recognition of Algeria as an independent country. By diving deep into the archives with an acutely present-day political viewpoint, and putting back together long-lost historic facts, she goes well beyond the often-seen pitfalls of Yugoslav nostalgia.

The breakdown of Yugoslavia

But there is certainly no nostalgia in Balls, a short film by Gorana Jovanović, screening in Best of Fests. The title refers to actual balls used in sport, but it is impossible not to read it as a mockery of everything macho and militaristic. This film also opens with archive footage, of the Hajduk Split - Partizan Belgrade football match in 1990 (ingeniously set to a Serbian-language, Yugoslav-era cover of "California Dreaming"), when Croatian fans set a Yugoslav flag on fire, another moment that is often cited as the trigger for the war, but was, like all aforementioned events, just a very visible symptom of the long-metastasized cancer. A more famous game several months later, between Dinamo Zagreb and Red Star Belgrade, which erupted in riots, was another. Through the connection between the governments, hooligans and organized crime, football has since been used to inflate national pride and create strife that subverted feeble attempts at reconciliation in the region.

With this in mind, all Jovanović had to do was make a stripped-down documentary without real characters or any relevant dialogue, in which army football teams of the six former Yugoslav republics gather for an indoor tournament in Sarajevo. The director films the Serbian team as they train, travel, arrive, have dinner, and get ready for the match. The way she chose to frame the scenes, in wide angles with a fixed camera, and what she decided to put in the film and what to leave out, gives it a gravity that transcends the joke of the title, and an atmosphere that perfectly fits all the ambiguities that this Pathway explores.

Balls

The audacious collage film Invoked, which screens in the Envision Competition, does not contain any nostalgia either, even if co-directors Srdja Vučo and Luka Papić decided to open it with Tito's death. The film is composed of archival TV broadcasts from the end of the eighties, when Milošević organized the infamous 1989 rally in Kosovo—another event that many see as the beginning of the 1990s wars—until the bloody anti-government protests in Belgrade in March 1991 and the beginning of the war in Croatia. At the center of the film are the first "democratic" elections (the filmmakers themselves insist on scare quotes) in Serbia in 1990, the election campaigns as they were broadcast on TV at the time, and interviews with five of then-presidential candidates. Having been political outsiders from the very start, today they are outcasts. Except for one, these men and one woman most certainly looked at the Yugoslav period as totalitarian, and it was a common thread at the time to trash communism and Tito left and right—not that a real "left" actually existed, as Milošević appropriated the Yugoslav Communist Party into his Socialist Party, embracing its heritage and denouncing its baggage.

Milošević knew that with his political and media infrastructure, inherited from Yugoslavia, he would face little competition. The more candidates there were, the more widely the votes would disperse, so the threshold was practically non-existent: 50 political parties took part in those elections. In a way, he was proven right, and as seen in Invoked, these elections were akin to a circus show with many colorful, eccentric, quirky, but always wholeheartedly invested candidates. On the other hand, the tyrant was not that confident, allowing for dangerous forces to gain momentum, as long as they went along with his genocidal vision of Greater Serbia. In the film, we can spot Serbia's current president Aleksandar Vučić, then a member of the right-wing Radical Party. This is where the alternatingly endearing and bitter tragi-comic mood of Invoked takes an apocalyptically dark turn, in the film's final music montage, with tanks heading to Croatia and leading us to the formally most complex film in this Pathway: Nataša Urban's The Eclipse.

Invoked

All the films in this Pathway use archive footage, and so does Urban’s, but she has also created something all her own, a sort of “simulated archive”. She filmed her documentary on 16mm for scenes happening in the present day, and on Super8, deftly manipulated to create a very old look, for those segments in which her family members relate their memories. Urban based the film on her father's hiking diaries from the 1990s, pinpointing the dates that coincided with key events of the wars of the time, asking him, her mother, and other members of the extended family how they experienced that era. Tellingly, Mom says: we are all trying to forget—why are you trying to revive those terrible years of poverty?

Facing one's own past

There was certainly poverty in Serbia, and I remember it well myself, but this was also the country whose army and paramilitary formations were killing civilians in Croatia, Bosnia, and Kosovo. Urban asks her loved ones the most difficult question: why did you not protest? The answers are, in retrospect, logical: they were trying to keep living their lives. Her dad escaped to his hikes and mom had to bake bread to feed the family.

I can remember my own family doing basically the same: when he was not struggling to make a living for all of us—and luckily, he had a job—my father escaped into reading books. Mom was also working, while grandma was baking bread, melting fat, and taking care of us kids—my sister just starting school, and me in the melodramatic throes of teenagehood. Can we judge Urban’s family, and mine? Should we? I don’t have an answer, but as Turajlić's film The Other Side of Everything shows, the war did have opposition in Serbia. But however vocal it tried to be, it got drowned out in the hysterical propaganda and all-encompassing nationalism.

The Eclipse

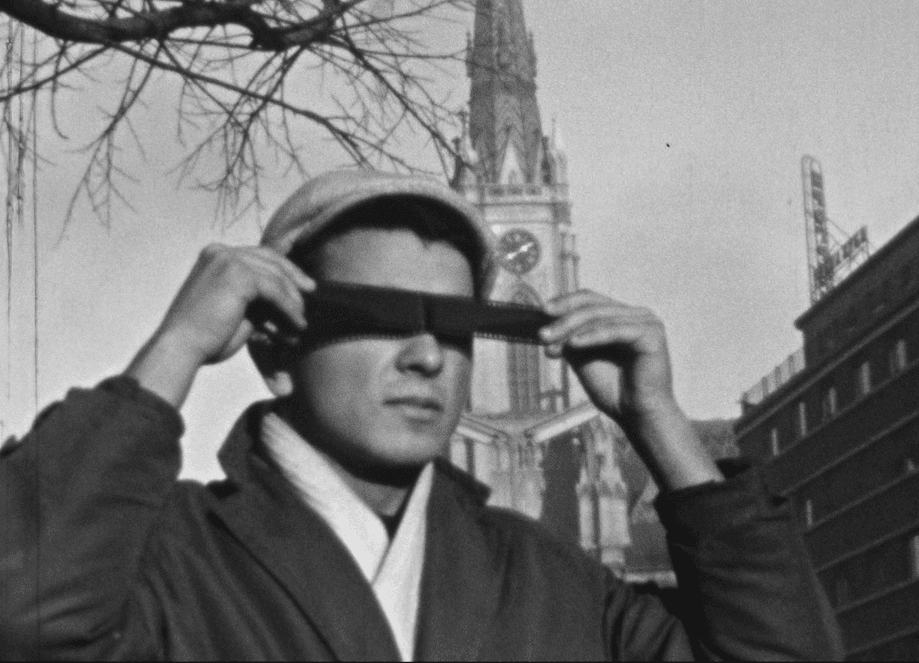

The title of Urban's film refers to the two total eclipses that happened in 1961 (interestingly, the year of the formation of Non-Aligned Movement) and in 1999, during the NATO bombing of Serbia. She correctly frames this as two completely different eras in her country: in 1961, Yugoslav TV encouraged viewers to experience this magnificent phenomenon, with instructions on how to avoid getting your retina scorched. In 1999, amidst the general atmosphere of fear, they were advised to stay home and pull down their blinds.

The hypocrisy of the NATO bombing itself notwithstanding, Serbia was indeed punished for its crimes, including the UN embargo of the 1990s. But has it understood and accepted its role? I know for certain that we are still a long way away from the ruling structures admitting to any of that. All the succeeding Serbian governments since the 1990s, even those considered the most democratic, steered clear from initiating such a process, afraid of losing votes from the people who have been fed lies and propaganda for 30 years. But this is why we have artists and filmmakers who unrelentingly pursue truth, reckoning, and catharsis.