Masculinities on screen: Sites of contestation and vulnerability

Lately, it has become a cliché to say that the concept of masculinity is in crisis or under erasure; in fact, feminists often joke that masculinity itself is a form of crisis.

What fascinates me about this—as a women’s studies scholar—is that the conservative moral panic over the status of what it might mean to ‘be a man’ within contemporary society appears to be predicated on the notion that at some nebulous point in history, we all implicitly understood what might constitute that most capacious of placeholders: Man. Far be it for me to demur with the entrenched historical perspective, except to say that feminists have never taken the term masculinity to be one of comprehensive classification, let alone to be indicative of a fixed, essentially defined category. It is from this perspective that IDFA presents this curated focus program entitled Around Masculinity. These films, I suggest, implicitly contribute towards a feminist project of questioning and deconstructing the norms and dictates of masculinity and seemingly patriarchal cultures. For in the wake of social phenomena such as #MeToo and the ubiquitous commodification of feminism by the neoliberal marketplace, it is, I feel, incumbent on all of us to understand and to historicize that which has functioned as the ‘neutral’ standpoint—the very center that holds—not only linguistically, but culturally, socially, and politically for so many centuries.

I believe that in 2022, we are meeting that reckoning head on. No doubt, it’s going to be a bumpy ride for a long while yet—evinced by the rise of the far right and its leveraging of attacks on those who wish to conceive differently of constructs such as gender or the nuclear family—but this work is underway; it there for us to see on our television screens, in the novels we read, in the pages of your newspaper, and up there, on our cinema screens. Around Masculinity considers central tenets of our most common conceptions of masculinity, opening up sites of contestation that admit of vulnerability, loneliness, the devastating effects of war on men’s psyches, of self-loathing and torment, as well as performativity and playfulness. Taken together, this is a powerful corpus that constitutes precisely the political and cultural labor I am suggesting is so necessary for all of us to undertake as a social responsibility to one another. Within the scope of this limited essay, it is an unenviable task to isolate highlights from such a rich and varied program: so, I can simply speak here to some personal favorites and humbly plea with you, the viewer, to indulge yourself in as much of what is on offer as time and money allows.

The Maysles brothers’ Meet Marlon Brando captures the star at the height of his fame and preternatural charismatic beauty. Embroiled in a press junket for the film Morituri, which he evidently has negligible interest in promoting, the documentary offers a commentary on the nature of publicity and celebrity itself. The Maysles have always been attentive to the arcane alchemy of individuality and performance rendered apparent by the mere presence of a camera lens (their Grey Gardens being perhaps the quintessential example), but here the studied use of the close-up and crosscut dissects and distills the seemingly ineffable magical presence of a star persona. Once you see it, you cannot deny it exists. Brando, the consummate performer, flagrantly modulates his behavior dependent on the gender of his interviewer. With men he oscillates between serious political agendas and banter (moving with ease between English, French and German), but with women, his genius as a performer becomes more evident: here is someone patently aware of his effect and affect, and he wields his masculine charm as prophylactic against intrusive questions. Ever aware of the presence of the camera, he turns it into his dance partner. In short, the Maysles become his co-conspirators here as Brando directs the camera towards the female form as precisely that which cinema (and Art) has nearly always reduced to being the object, but never the subject of the gaze. Re-watching this short, entrancing film, I could not help but think of Johnny Depp—a younger disciple of Brando—who also knows exactly how to leverage his charm against the camera, while implicitly putting women back in their place.

Meet Marlon Brando by Albert Maysles and David Maysles

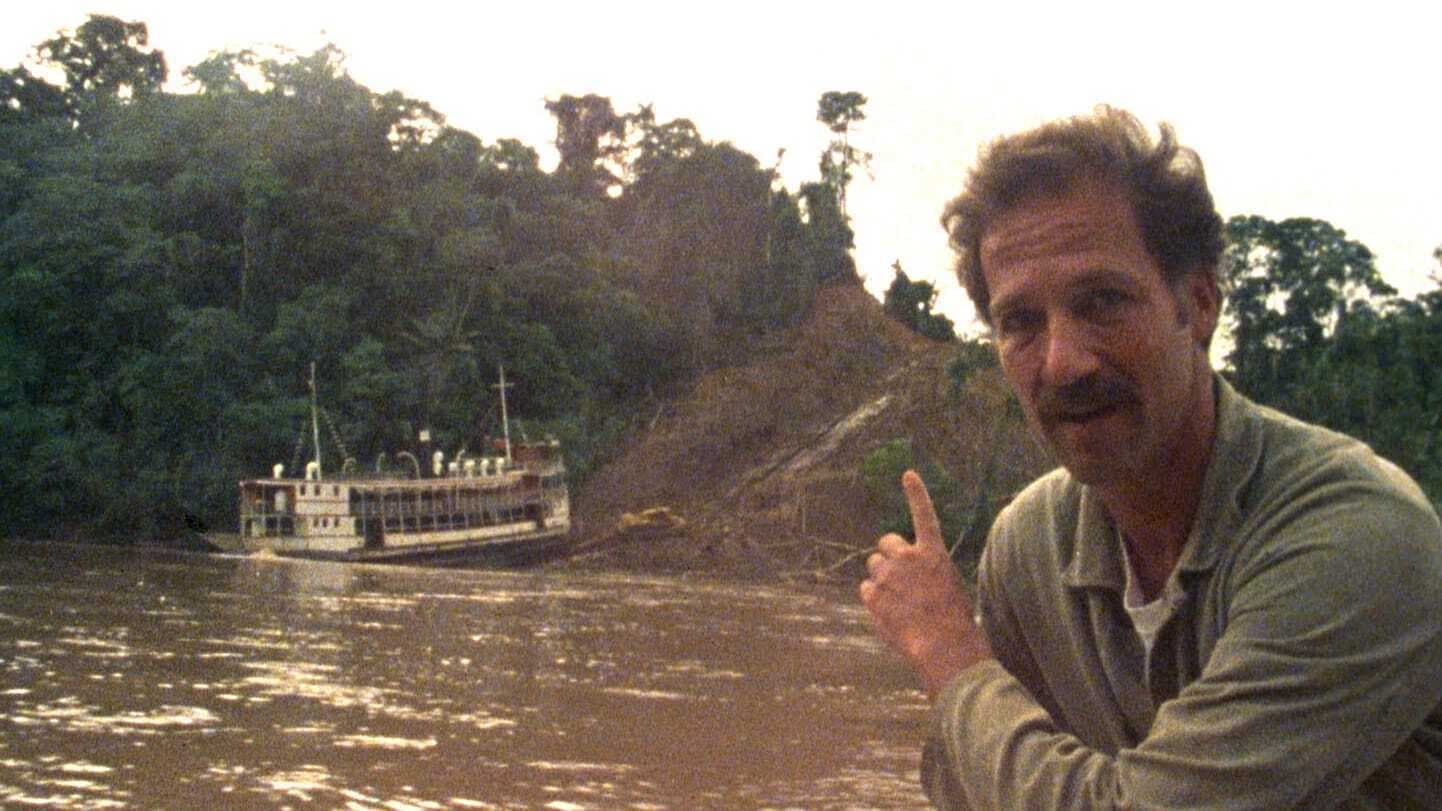

In Les Blank’s Burden of Dreams, we turn to that most Romantic of figures: the lone male artist or auteur. Here, the filmmaking experience is beset by weighty existential meaning and high seriousness, a task through which Werner Herzog pits himself against the cruel and base indifference of nature, as he so bombastically conceives of it. Cast as the heroic figure within a grand narrative of his own making, Herzog has no time for the seeming trivialities of the effect his artistic endeavor may be having on the Indigenous population and embattled landscape around him. At once both compelling and infuriating, Herzog risks madness and death in his stubbornly Sisyphean dedication to his own visionary genius. The Amazon jungle becomes a projection of the male auteur’s mind—a land created by God in anger, as a vile curse that weighs on the artist’s very soul as if to spite his hubris. Only fleetingly does Herzog admit to himself that it is he, a self-styled God of Cinema, who is the maker of his own folly, daring to tilt at a world he cannot hope to master. The resulting images are undoubtedly sublime but provoke ethical dilemmas about the consequences of unchecked artistic ambition.

Burden of Dreams by Les Blank

Andrea Luka Zimmerman’s Erase and Forget partakes in what I would term masculinity ‘under erasure’. Filmed over a decade, it relates the story of James Gordon ‘Bo’ Gritz (one of the most highly decorated soldiers in American military history, and the supposed real-life inspiration for cinematic heroes such as Rambo) and his growing disillusionment with American politics and conservative cultural identity. Masculinity comes to be understood as a destructive form of madness, a traumatic wound, that is both the direct product and casualty of a relentlessly patriarchal, patriotic, and paranoid form of political ideology. Zimmerman’s cinematic triumph lies in the ways in which she reveals the imbrication of America’s hidden wars with the cinematic image itself. And just as the emergence of the hard, white, masculine body of 80s action films directly emerged from Reaganite politics as a response to the ‘softness’ of Jimmy Carter’s tenure as president and the humiliating failures of American foreign policy during the 70s, Erase and Forget reminds us that all manifestations of such resolutely robust masculinity are an effect of powerful forms of repression. Eisenhower may have warned of the consequences of the military industrial complex, but arguably just as pernicious, suggests Zimmerman, is the carefully calibrated relationship between the cinematic body and the body politic itself as mutual forces of co-creation. Gritz emerges as an incontrovertibly damaged individual, ‘spiritually undernourished’ and fatally isolated. As he says in the film’s closing moments, soldiers often shoot themselves not in the head, but in the heart: that’s where the pain is.

Erase and Forget by Andrea Luka Zimmerman

Finally, the late Heddy Honigmann’s extraordinary film Crazy, about the UN peace keeping force, centers on the utilitarian logic of warfare and the long-term damage this causes in individuals who are fortunate enough to return from the totalizing hell of war; that logic, employed by politicians and NGOs alike, is shown to be a strategy that renders all emotion at best a luxury, and at worst a liability. Honigmann’s film dares to ask how one might cope with the daily business of repressing deep trauma merely in order to live in the present moment. Those who cannot name what they have seen can express it only somatically in her film—the fevered brow, the forced smile or laugh, the darkest expression of humor, the continual attempts to self-medicate and stay busy; but those who do try to find the words to say it perhaps fare no better in admitting of experiences so horrifying that they obliterate any possibility of exhaustive understanding, lodging only in the memory as shards of madness. It is the utter meaninglessness and purposelessness of all human suffering around which the film’s subjects circulate in their evidence offered to the viewer, for which only music can be found as the emotional correlate. This is not masculinity simply in crisis on display here: these are men mentally plagued by what they can never unsee or unhear. This uncompromising and tender film tells us that war as an act of pervasive brutality not only salts the earth but makes casualties of the human heart. It warns of what each one of us may be capable when desperately driven to survive under the very worst of all possible circumstances. It reminds us that once we have experienced that fracture in our daily reality, there can never be any spotless, innocent place to which it is possible to return. It presents masculinity as a haunting.

Crazy by Heddy Honigmann

In this brief, and selected, overview, I have tried to offer an impression of the manifold ways in which this program does the work of feminism by interrogating the very nature of what we take to be the masculine position and, more specifically, what that position is made to stand in for, or to speak on behalf of socially and culturally. IDFA proffers not only a public and democratic education in this sense; it also partakes in a global conversation about how we inhabit our bodies as political agents through the expression of gender. None of these films offer simple or trite solutions to our currently fractious and frightening political climates, but they do provoke necessary and vital questions about a future in which we may all be able to experience gender not as a deadening prescriptive blueprint that defines us as male or female before we have had the chance to become a person, but as something we might be able to inhabit with lightness…dare I say it, even with a little joy?

About the author

Anna Backman Rogers is Professor of Aesthetics, Culture and Feminist Theory at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Her previous publications include American Independent Cinema: Rites of Passage and the Crisis-Image (2015), Sofia Coppola: The Politics of Visual Pleasure (2019), Still Life: Notes on Barbara Loden’s Wanda (2020), and Picnic at Hanging Rock (2022). She is also the co-editor of three books on feminism and visual culture with Laura Mulvey and Boel Ulfsdotter respectively. She is the founder and editor-in-chief of MAI: FEMINISM AND VISUAL CULTURE.