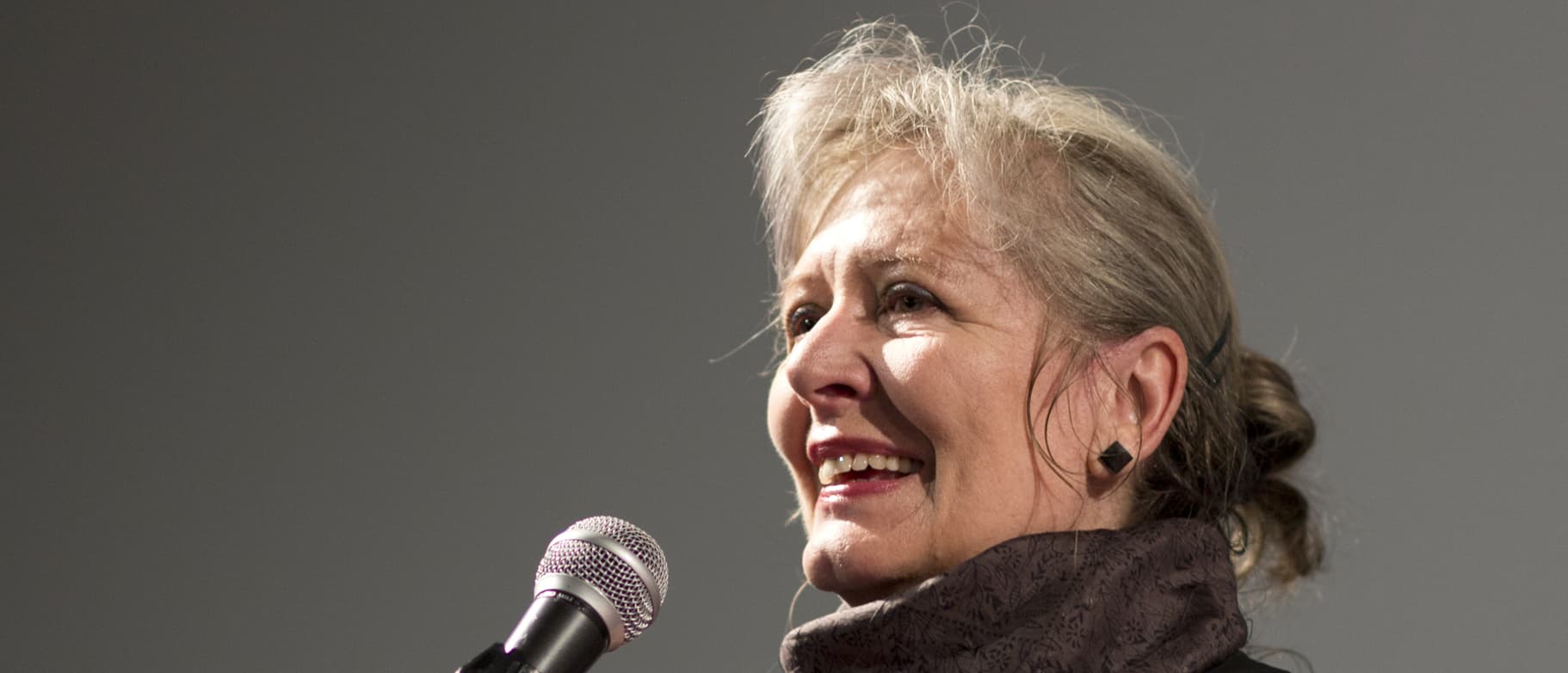

Guest of Honor Helena Třeštíková on her Top 10

"Choosing the 10 most important films of my life is a beautiful but challenging task. Since being given it, I have been thinking about my favorites and watching my life flash before my eyes."

Even as a child I was an avid film buff. I went to the cinema as often as I could as we didn’t have a television at home. One day, an earthshaking experience came along: I saw the movie Something Different (O necem jinem, 1963) at the age of 14, and it was something akin to being struck by lightning. Part documentary, part live-action film, reality and narrative fiction come together and the whole thing is utterly truthful—as opposed to most Czech films of the time, which stick to the mandatory canon of “socialist cinematography” and portray characters that are not true to life in the least. I also saw the film as a powerful infiltration of freedom into our vapid little world.

I read the credo of the film’s young director, Věra Chytilová: “A film should have truth, aesthetics, intellect, feeling and a belief, because film should be true, exciting, necessary, beautiful and full of hope”. So, I wrote in my diary that I’d like to make movies. It was a completely absurd idea at the time, and I didn’t tell anyone because they would have laughed at me. But one thing I know is that Věra Chytilová changed my life that day.

The Firemen’s Ball (Hoří, má panenko, 1967) — another key film in my life.

A local fire station’s ball in a small Czech town. The drabbest characters imaginable create an allegory of society before our eyes. The Italian film mogul Carlo Ponti took part in the project as a co-producer. When he saw the final product, he was horrified and wanted his money back, saying the movie ridiculed the common man. Its director, Miloš Forman, was charged with misappropriation of funds and faced 10 years’ imprisonment. Luckily, French director François Truffaut found out about the movie and he and some colleagues bought it and gave Ponti his money back. But, no sooner than it was completed, the film was banned in Czechoslovakia. Then the Prague Spring came along, official censorship ended and the film could be seen, though not for long. After the arrival of the Soviet tanks, censorship returned for 20 years. It’s interesting to note that both communists and a big capitalist producer alike were so vexed by an honest glimpse of life. The Czech New Wave in film was a fundamental impulse for my endeavor to become a filmmaker.

And in 1969, my dream became reality: I became a student at FAMU [the film and television academy of Czechoslovakia], and eagerly devoured every movie they showed us in the history of documentary film class. Sometimes I even passed the tests on them.

Farrebique - The Four Seasons (1946)

Over the course of a year, Georges Rouquier observes a family of farmers in the French countryside. It’s the normal lives of normal people that fascinate me—the ordinary, the everyday. No artificial stories or fabricated drama. I said to myself, now that’s documentary filmmaking! A major inspiration.

A cinematic poem with beautiful camerawork and wonderfully selected music by Joris Ivens, based on a screenplay by Jacques Prévert. I’ve seen other films by Ivens such as Borinage, but I found him to be more powerful as a poet than an activist.

This half-dramatized documentary captivated me with its splendid portrayal of 1950s America. A newly-divorced woman holds an imaginary conversation with her alter ego (or perhaps with her conscious). She falls into a depression, wanders the city at night, meditates over the course her life, gets in a car accident and returns to life. All this plays out among the diverse and sometimes bizarre inhabitants of a big city, and all of it is beautifully filmed in captivatingly artistic black-and-white cinematography.

As a student, this was a film that made me think about how the possibilities of documentary film are limitless, and that it would be beautiful to spend my whole life investigating them!

I finished school, and I was cast out into the real world, looking for myself and my place in filmmaking. Our world at the time was very confined by the political dynasty of one party, there was heavy censorship, the borders were closed, foreign documentaries were not shown. It was a little Czech pond with no great horizons. And that became my theme: the everyday little things, the ordinary little lives around me. Then I got the idea to observe these everyday stories over a longer period of time. I found the theme of my life’s work: longitudinal documentary.

There was not a lot going on in Czech cinema after the Soviet occupation, but from time to time something extraordinary came out nonetheless.

Prague: The Restless Heart of Europe (Praha - neklidne srdce Evropy, 1984)

This is part of a series of films about important world metropolises shot by prominent directors. Věra Chytilová was a brilliant filmmaker, and she handled the topic in a unique way. Together with the superb cinematographer Jan Malíř and editor Alois Fišárk, she created a fascinating poem about Prague. In the process, an exceptionally vibrant film was made during a time of political stagnation, which was absurd, really. It also took a while before it could be shown. Chytilová’s film never gets old, and it could be seen as a textbook example of the possibilities allowed by film language and expressing oneself specifically through film.

In 1989, our lives changed. The communist regime collapsed, the time for free elections came, censorship ended and the borders were opened. We all took in a breath of air, and filmmakers looked for new themes.

Citizen Havel (Obcan Havel, 2008)

In 1992, I was present for the historic meeting where director Pavel Koutecký told then-president Václav Havel that he would like to follow him with a camera for 10 years. Havel agreed, thus clearing the way for one of the most noteworthy long-term film projects whose protagonist was a politician in office. Havel was extraordinary in many ways: originally a dramatist, then a dissident, prisoner, and after the revolution a president. He allows himself to be filmed in situations where other politicians would immediately shoo a filmmaker off. But he gives Koutecký and his crew his full trust. Part of the agreement was that the film would only be released five years after the president’s term in office. But the director tragically died just as the film was in its final stage, and it was completed by his colleague, Miroslav Janek, in 2007. I think that no one will ever make such an open film about a politician and his times again.

The world opened up to us; from time to time I had the opportunity to visit film festivals abroad and I looked for projects from other countries similar to what I was trying to do. Films about normal, everyday people, and longitudinal documentaries.

I come across the project 7 Up by Michael Apted and all kinds of variations on the format. I was most taken by the Russian one, Born in the USSR. Director Sergei Miroshnichenko had taken the 7 Up format, observing a group of about 15 children for seven years in seven-year intervals. In this Russian variation, all of the children were born as citizens of the Soviet Union, but the USSR broke up into individual countries a few years after the start of filming. It is fascinating to watch the very different fates of the children selected. In this case, major historical events have heavily impacted the minor stories of human fortunes.

First Love (Pierwsza milosc, 1974)

I admire this project of Krzysztof Kieślowski’s, in which he spends a year observing an average young couple expecting a child. Kieślowski originally wanted to follow them for a longer period of time but ended the project after a year. I read that he was concerned about how filming any longer would affect the young couple’s lives. At the same time, I was filming a similar topic, originally a 15-minute project entitled The Miracle (1975), and I went on to observe the family for another 37 years, giving rise to the film Private Universe (2012). Like Kieślowski, I too pondered the issue of the how the film might influence their lives, but I reached the opinion that there was no danger as long as the rules of ethics between the director and the protagonists were adhered to. Nonetheless, it is an important issue in documentary filmmaking. I am a little disappointed that I will never find out what became of that young couple. Nonetheless, the film First Love is an example of Kieślowski’s amazing sensitivity as a filmmaker and of his skill, which he continued to refine in his narrative films.

In Slovakia, I was struck by the work of a young and utterly original director, Peter Kerekes. In 66 Seasons, the public swimming pool in Košice becomes a metaphor for life itself. Birth, death, love, attraction and hatred, all reflected in a fascinating form of filmmaking without ever even leaving the pool and environs. I consider this a beautiful example of inventiveness in filmmaking, imaginativeness in direction and walking a tight rope in editing. For me, it is something of a textbook for the opportunities of using film language in a documentary.

I am fretting over my selection, thinking maybe I could have been more specific. There are a number of films I’ve missed, and lots of things I’ve forgotten. But I’ve known for a long time that perfection is unattainable, and I will always fret…

Hopefully, my selection of films will find an audience who, as I do, considers them in terms of the beauty of cinematography and all of its endless possibilities and vastly unexplored directions.

Trestikova