In Focus: "Me"

A program all about “Me” suggests a few things, some of which turn out to be correct, others mistaken. This amazing program features films from the 1970s to today, ranging in approach and technique from the epistolary avant-garde of Chantal Akerman’s News from Home to the clay figurines of Rithy Pahn’s The Missing Picture. It’s an investigation into the personal filmmaking that has been transforming documentary for decades. The films all foreground the experience of the filmmaker in some way and emphasize the subjective point of view. But miraculously, these films aren’t just self-absorbed exercises in navel-gazing, as the title might also suggest. More than the first-person singular perspective that “me” implies, the personal and avowedly subjective use of this medium is actually much more about the first-person plural, making it a cinema of “we.” To focus on oneself in a film is no more an act of self-indulgence than it is in the writing of a memoir or diary, or a poem for that matter.

And yet, why shy away from the personal here? Why insist that these films have to be engaged in looking outwards towards representing “others,” to the extent that many other documentaries are? What if we were to also find room in the vast arena of documentary practice for those films that interrogate personal problems, family dynamics, relationship issues, the loss of a beloved dog? Why not make space for those films that contravene the invisible boundaries of the private, revealing the foibles, the vulnerabilities and the emotional complexities so often obscured in more polite, more distant approaches to representation? Indeed, why always maintain a distance, or perhaps more to the point, why should we be allowed to point a camera into other people’s lives and not interrogate our own? It’s the very act of self-representation and the representation of those close to us where we begin to understand the limits of the private, the bounds of the sayable, the expressive borders that circumscribe our lives.

When a filmmaker makes a film to work through his unresolved relationship with his ex-girlfriend, or her complicated yet loving relationship with her adoptive parent, or even his right to complain of a headache, aren’t they using the medium as much as a psychoanalytic device as a technological one? Isn’t there something truly interesting and revelatory about this fact? Film scholars have long been fond of engaging psychoanalysis in the service of interpreting fiction films, but this opens up a whole other dimension where the filmmaking itself is subject to analysis, as it were. While practicing without a license may be unwise, it’s still interesting to think about film as a type of psychoanalytic space—a prosthetic device that may help a filmmaker work through their deepest traumas or their most pressing conflicts. One of the early dreams of cinema was that it could become as expressive a medium as pen and paper, or paintbrush and canvas, as immediate, as reflective, as personal. Every single film included in this section is testament to the fact that all around the world, filmmakers have indeed adapted this unwieldy apparatus for the clearest expression of their innermost thoughts.

Let’s return to the claim that this type of personal filmmaking, this “cinema of me” is also always a “cinema of we.” So many of the themes developed in the films of this program manage to touch on universal themes, transcending even while displaying their own limited cultural milieu or personal preoccupations. When Pawel and Marcel Lozinski head out on their father-and-son road trip that exposes the unresolved pain in the wake of a harrowing divorce, we’re suddenly not in a car driving in Poland but in our own memories and experiences of the brokenness of nuclear families. And if we have never experienced the divorce of our parents or the loss of a family member, or the displacements and traumas of war, we’re fortunate to have these talented filmmakers using all of the creative means at their disposal to communicate something of those experiences to us.

Even when the theme couldn’t be more myopically focused, as with Viktor Kossakovsky’s Wednesday, about people born in Leningrad who share the same birthday as the filmmaker, the themes that emerge are nothing short of existential: the meaning of existence, the randomness of birth, the belief systems surrounding questions of fate are all contemplated by the quirkily untutored participants in this film. Distance, alienation, loneliness, fear of abandonment, exile and loss are themes that run through many of the films in this selection—themes that resonate well beyond the intimate concerns of the filmmaker him or herself.

Some of the filmmakers featured in this section are inveterate first-person filmmakers. Ross McEllwee, for instance, made his presence behind the camera a signature of his filmmaking practice, from the time he made Sherman’s March in 1985 right up through today. Avi Mograbi in Israel and Andrés Di Tella in Argentina are also mainly known for their first-person films. Others, like Naomi Kawase or Chantal Akerman, contribute important films in this personal vein but are better known for their fiction films. These may traverse some similar themes, but they don’t necessarily make the filmmaker’s personal story explicitly evident. Rithy Panh, for his part, has made several documentaries and a handful of fiction films, but The Missing Picture and his new film, Graves without a Name, are by far his most personal films, depicting his memories of life and death under the Khmer Rouge. For Panh, in line with the majority of the filmmakers included here, the first-person address is reserved for those films that simply couldn’t have been made otherwise. It’s much less a question of self-indulgence, and much more the urgency to communicate a complex formative experience (very often a trauma) that leads a filmmaker down this path. These are films that were burning to be made, and the experience of watching each and every one of these films forged in the furnace of the soul, makes a deep impression on us. These films aren’t easily forgotten, so come prepared to be profoundly affected.

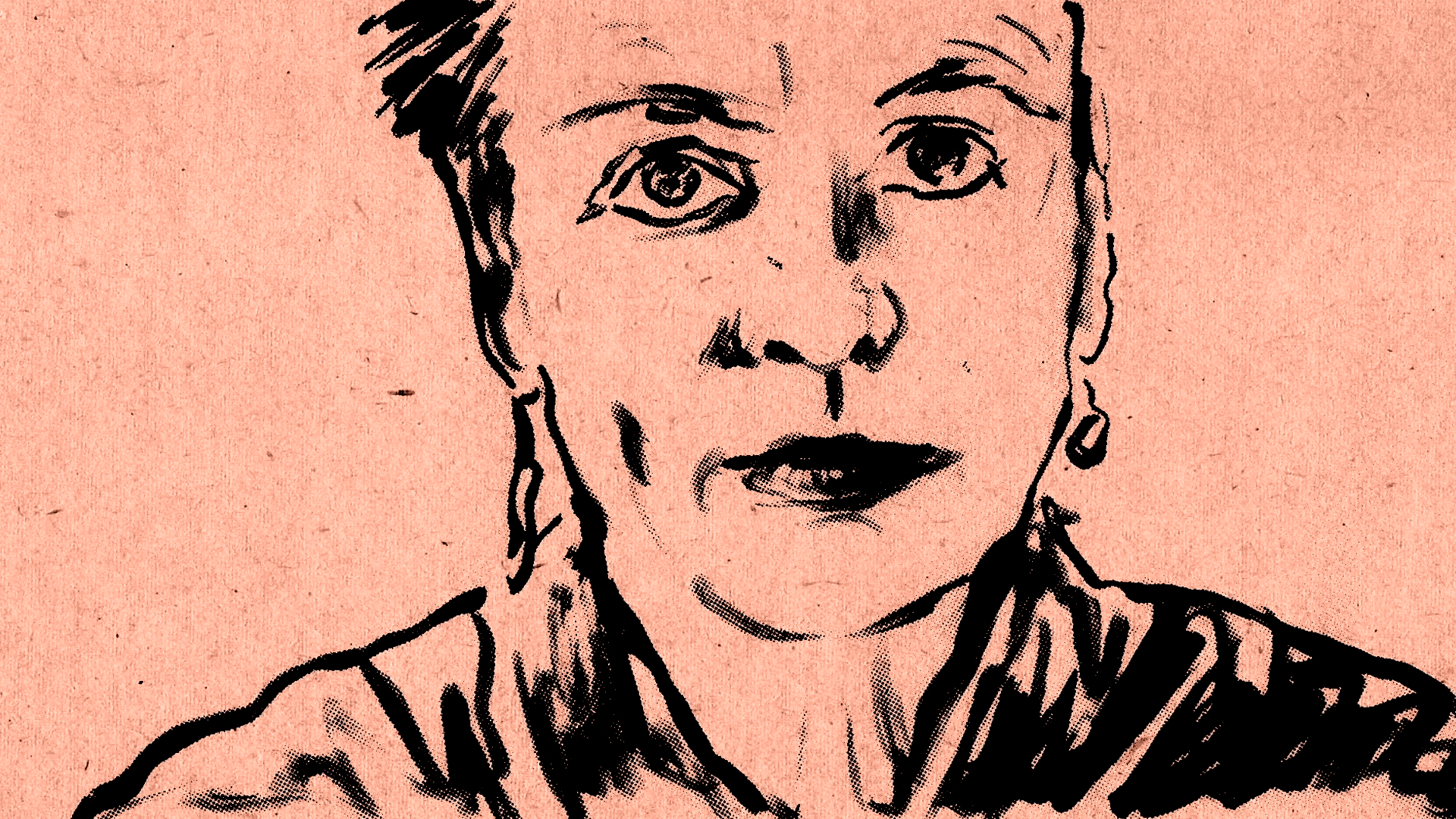

Alisa Lebow is reader in Film Studies at the University of Sussex and editor of the book The Cinema of Me (2012). She contributed to IDFA’s focus program Me as senior advisor and will interview some of the filmmakers in the program during the festival. In addition, Lebow is a member of the IDFA 2018 jury.