Karim Kassem on filming the silence after the Beirut explosion in Octopus

Lebanese director Karim Kassem made his second feature-length film this year, Octopus, spontaneously and almost incidentally: he was visiting his home city of Beirut when the port explosion happened in the summer of 2020. Sitting down at the end of the festival, he tells us how he made the dialogue-free docu-fiction hybrid which garnered him the newly established IDFA Award for Best Film in the Envision Competition.

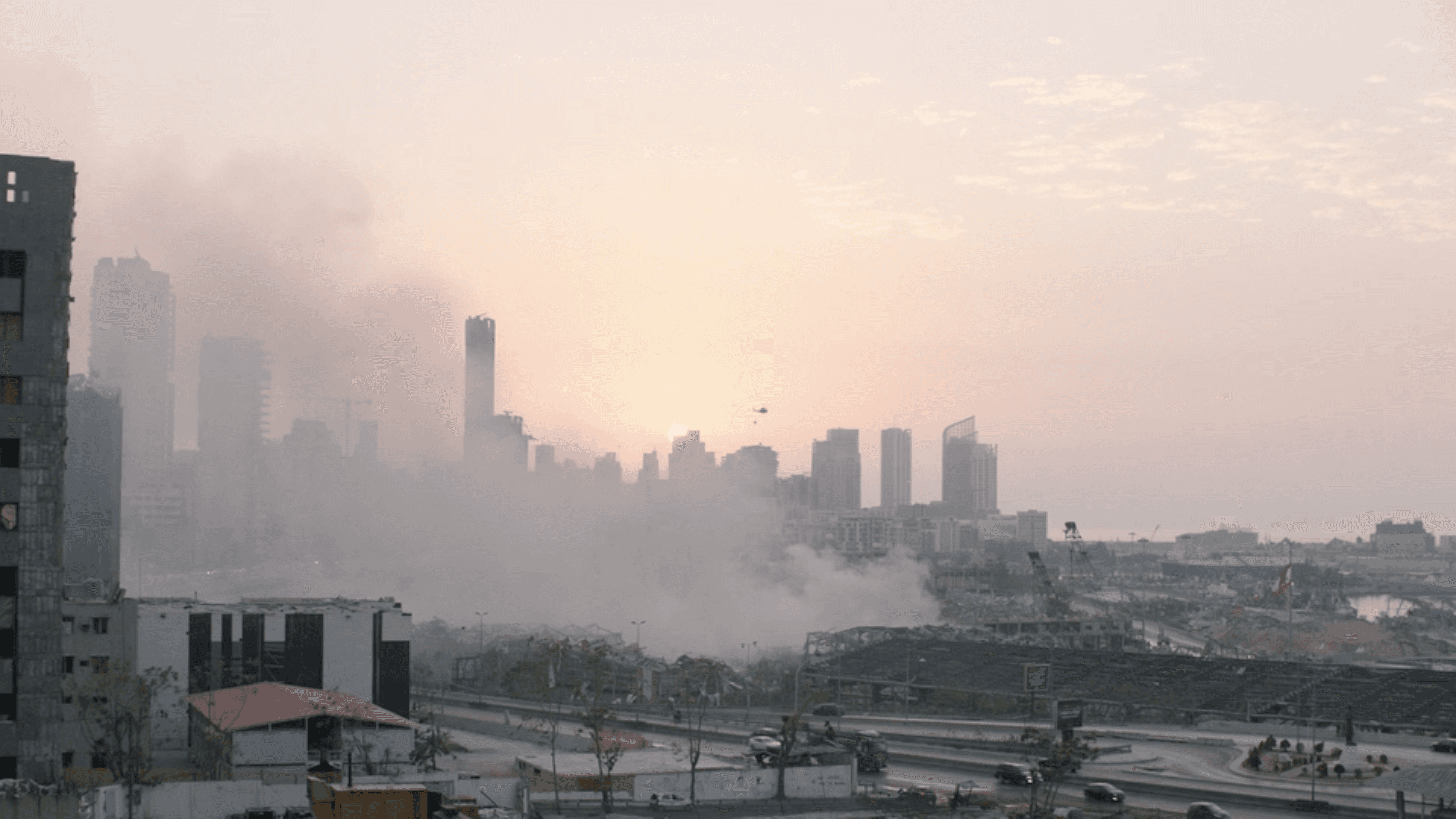

The Beirut-born, New York City-based filmmaker Karim Kassem landed in his hometown on August 3, 2020 and had to quarantine in a hotel room due to COVID regulations. The hotel was facing the Port of Beirut, where the next day a large amount of ammonium nitrate exploded, causing at least 218 deaths and 7,000 injuries, and leaving more than 30,000 people homeless.

"I was blown out of the room," he remembers. "I literally ran for my life; I saw the shockwave coming and I ran in the other direction."

Kassem believes this first-hand experience of the explosion is what informed his approach to the film he made about it, Octopus, which has triumphed in the IDFA Envision Competition. There is no dialogue in the film, only footage of the city and the people living in it. Sitting in their demolished homes or shops, they seem frozen in time: the director films them as they appear to look into the distance, shell-shocked, in silence.

But how does one film the silence of the aftermath of such a tragedy? How do you knock on someone's door with a camera and say, I know you just almost lost everything, maybe even lost someone you love, but can I film you for a little bit?

"It was very difficult because I had to approach everyone," Kassem recalls. "But it was also a little easier for me because I experienced the explosion myself, so the conversations that took place prior to setting up the camera were imperative to get access into their world. Some of them rejected me very bluntly, and some let me in, made coffee, and we spoke for a long time. I decided to film the silence after these conversations."

Of course, this was not simple. Many of his protagonists felt the need to describe what was happening to them on camera as well. But Kassem says he tapped into an energy that they all shared and he recognized.

"There was an energy that people were feeling that was very confusing, but pensive and philosophical," he explains. "And being a philosopher to some degree myself, I felt that maybe expressing this silence was pretty easy: the feeling was already there inside of them and I knew that. Even though sometimes it was hard to get to it, I had to calm things down before filming, so there was a state of limbo in between."

Philosophical and instinctual

Kassem's background in philosophy is not academic. He says he was never good at tests or grades. But he studied it extensively and rigorously, and when he talks about it, one cannot help but spot the contrast between his very intellectual verbal expression and the evidently instinctive nature of his film. But eventually, it turns out that the philosophical and the instinctual for him come from the same place.

"Nature is instinctive," he says. "I'm philosophizing my view of the film, but at the same time, the film doesn't say anything. It is just a different way of expression, another language."

"The fundamental thing that this film really tries to tackle is this idea that the world is of mental nature," he continues. "The physical is just an appearance of something else. This is something that I'm echoing through cinema because we are living in a materialist paradigm and culture. This film is sort of just poking at that and saying, 'Hey, pause, let's be silent and think about where we are going. What just happened?'

"Regardless of whether there was an explosion, we should sit down and think about where we're going, and that's what I kind of instilled into the non-actors to get that performance from them. I don't think it was a performance; it was real, but there was a lot of fiction in the film. The line gets pretty blurred."

Filming and editing the docu-fiction hybrid

Like his other feature-length film this year, Only the Winds, which world-premiered at Visions du Réel, Kassem describes Octopus as a docu-fiction hybrid. But his approach to filming and editing in this case was certainly more documentary-like.

"It was very spontaneous, no one planned for the explosion to happen," he recalls. "The whole shooting was done by me and two more people. We were sitting every morning in the back of the parking lot and thinking what we're going to do, what we're going to explore that day.

"The same goes for editing: it was also instinctive. I had a vision of where I was going to, I just didn't know how to get there with all the imagery. I have to thank my editor Alex Bakri; he did such an amazing job in just pulling things together and throwing ideas at me."

What stands out as an impression when watching Octopus is the respect and dignity with which the protagonists—or non-actors, depending on which angle you decide to take—are treated.

"At first we had a completely different ending, with a segment of about 14 minutes with talking, and the whole film was 80 minutes long," he reveals. "We showed that to people and there was a debate, and at the end I was convinced that the way we ended up going about it was more respectful, subtle, and pensive. In essence that's what the film was really about; it was about respecting everybody in the film, and not just about my vision.

"There is really no other way," he continues. "Someone asked me at the Q&A, why didn't you show the civil unrest? Many filmmakers made documentaries about the revolution since 2019. But I try to avoid the noise, because noise is very attractive, it pumps you up, it makes you want to say something... But taking that pause and thinking about where this is going, is healthy."

Symbolism of the octopus

At one point in the film, one of the protagonists paints a picture of an octopus on a wooden plank. This is as explicit as Kassem would go in elaborating the symbolism of the title in the film itself.

"I can't answer the question literally because this sense of literal truth is new in the history of humanity," he says. "Apart from that, we live in a world of symbols, and this is another symbol that is pointing to a sort of transcendental truth, pretty much like religions do. So, in essence, I can't really answer the question what the octopus is, because if I do, it defeats the purpose of what it is, and I would be destroying the meaning that you can conceive of through the octopus."

He says that some people saw it as a symbol of corruption, others of regeneration.

"And I can tell you 3,000 interpretations of what the octopus means in the film, and none of them would be wrong," he muses. "But the way I see it, these octopus tentacles represent different minds within one mind: we are all connected, but we have different perspectives, and each tentacle can have its own perspective under this one mind.

"If we erased all our memories, we would go back to the essence of what we actually are, which is pure awareness. To me, metaphysically speaking, this is what the octopus represents. That's one idea. The other could be that it is an ode to the sea, because 60% of the explosion went into the sea. If it didn't, today there would be no Beirut."