Peter Greenaway receives Lifetime Achievement Award

The great British filmmaker showed a work-in-progress version of his latest film and spoke about his beginnings, career, views on art, cinema and the documentary funding system.

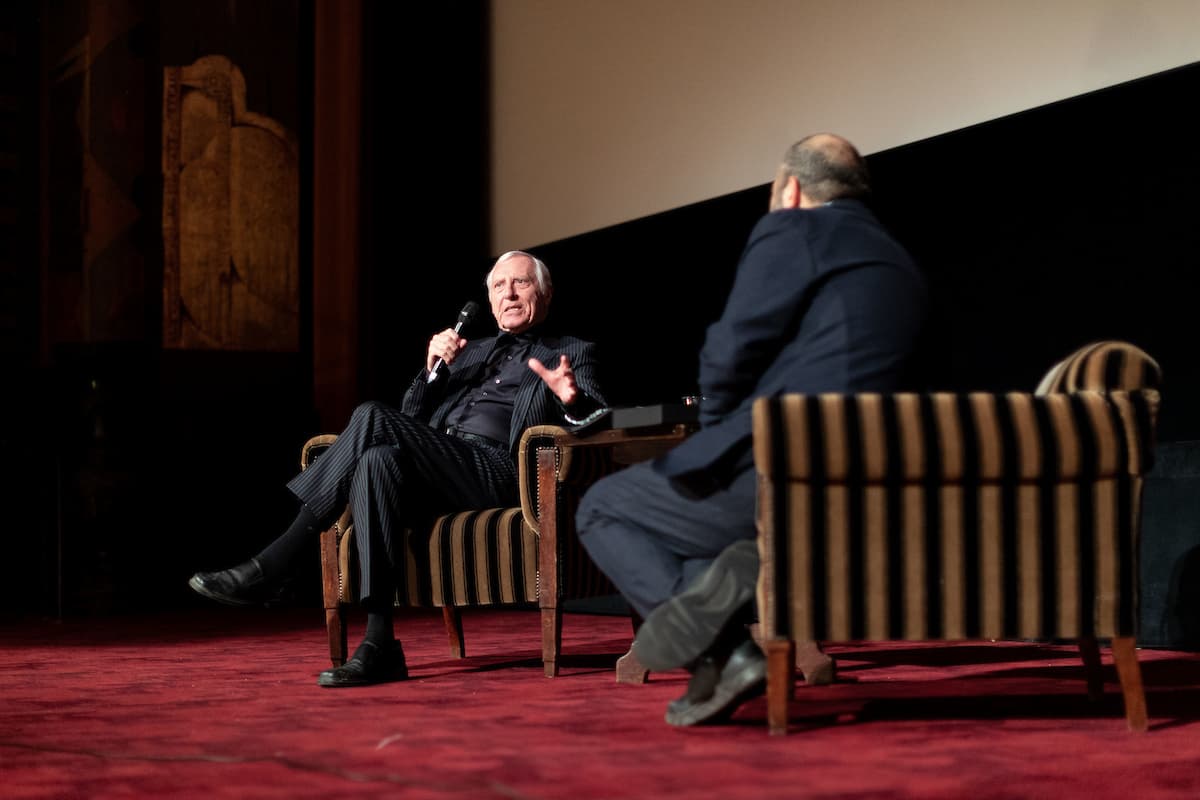

On Sunday night in Tuschinski, British filmmaker Peter Greenaway received a Lifetime Achievement Award from IDFA's Artistic Director Orwa Nyrabia.

Before presenting him with the prize, Nyrabia introduced Greenaway as a filmmaker who has created his own genre. “Every time I see a Greenaway film, I see something new,” he said. “It's always something I'd never seen before, and he is still always himself. And what is it exactly? Is it documentary? Not really. Is it fiction? Well, it looks a bit like documentary.”

“That's why I deeply believe that there's a genre of film called the ‘Greenaway genre’. In the Greenaway genre, you're taken somewhere with this wonderful artist, filmmaker, who is trying always to examine what is cinema, how cinema can be an artform of its own.”

In his trademark deadpan style, Greenaway thanked Nyrabia for these complimentary words, responding: “I deny them all.”

“If I have any reputation at all, it's more in the fiction world than it is with the documentary, but I understand what you said. And for me, the categories are not very useful.”

Now 81, Greenaway said he hopes he has another ten years in which to finish some of the many projects bubbling inside him – he currently has five feature films “ready to go”, as he put it.

The audience were then treated to the work-in-progress version of his new film Walking to Paris, about how the great Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi started his career by walking from Bucharest to Paris.

“It’s part fact, part fiction; I can’t prove anything, but you can’t disprove anything either,” Greenaway joked, stating that he is happy with what he believes is an “85% finished film”.

The film follows the 18 months it took Brancusi to reach Paris on foot, and all the ensuing adventures that went on to inform his art.

“It was like an apprenticeship for him”, Greenaway explained.

After the screening, the filmmaker and IDFA’s artistic director engaged in a conversation which started off with a question about Greenaway’s own apprenticeship.

“My first attempts were on an 8mm camera, and then on a Bolex 16mm black-and-white camera, which taught me discipline – it only had a spring loading [mechanism] which would allow me a shot up to 17 seconds long”, he recalled.

Living in rural Wiltshire, from the very beginning Greenaway felt a deep connection to the natural world.

“As an adolescent, that particular association with natural history became more sophisticated for me when I discovered evolutionary theory, and Darwin became a great hero of mine”, the filmmaker said.

This interest later translated into a passion for the art of painting.

“The idea was to try to find a new way to examine landscape, like Turner or Rembrandt; that the landscape had to be in some ways illustrative of some extraordinarily exciting work. William Morris essentially was a great influence, and all the time I had my eyes very firmly on nineteenth-century English painting”, Greenaway said, explaining how his film Drowning by Numbers was an attempt to go back to these roots.

Greenaway learned his craft at the British Film Institute, taking care of the distribution of archive materials related to the Central Office of Information, which he joked sounded – and in fact was – rather like a Soviet politburo. He connected this propaganda aspect to his affinity for Eisenstein and the classic director’s “cinematic intelligence”, which Eisenstein was able to employ when not working in Russia – as explored by Greenaway in his 2015 film Eisenstein in Guanajuato.

With all this in mind, Nyrabia asked Greenaway about his frequently stated belief that cinema is not an intersection of other arts, and should not be based on literature or a script.

“The Bible says, in the beginning was the word – that’s rubbish”, Greenaway bluntly put it. “We haven't been writing for very long, but we’ve had painting for at least 45,000 years. So there’s a great discrepancy there. We are 128 years into the history of cinema, so there’s no comparison. And I would imagine that, through these 128 years of watching millions of films, there should have been a far greater sophistication in cinema.

“I’m delighted that you’re here in the audience; an audience which must certainly be greatly interested in cinematic perfection, examination and experimentation. But despite all the sophistications, all the gizmos, the actual ability to manifest the natural world on film is still lacking a certain mystique, a certain mystery, a certain excitement, however much we’ve created great heroes of cinema”, he mused.

“I think of Tarkovsky, Bergman; many purveyors of fascination with the world that we live in. But still, that sense of contemplation is somehow curiously missing. I thought DVD would answer this question somehow, that there would be a way to rework, refashion, reorganize, but the DVD has virtually disappeared from our landscape now. Similarly with 3D, this huge revolution that was supposed to take place never happened. But there is a way, and I will still be very conscious of new technologies.”

Nyrabia then reminded the audience of how involved Greenaway still is in this search: he was leaving the next morning to film in the town of Lucca in Tuscany. But not before Nyrabia asked him about his view of documentary cinema.

“Your relationship to reality and research is a very consistent part of your film language. So your fiction is always full of those documentary elements, but still it is your imagination that is filmed. Can you tell us about that – because you used to be a very harsh critic of documentary as a notion?”

Greenaway responded with a statement that drew long applause from the audience: “It is inhabited by notions of financial and political freedoms, which certainly have to be promoted, encouraged. But is it not extremely ironic that you now have to virtually write a script before you can find money to make a documentary? That seems to be a profound contradiction, an oxymoron which ought to be put right.

“I mentioned my beginnings with the Bolex camera, the sheer excitement of those years when I could take a camera and simply film the world, and then make a discovery about how to organize that, how to authenticate it, validate it afterwards. For me, those were the halcyon days when I really did feel I was a filmmaker.”